Introduction

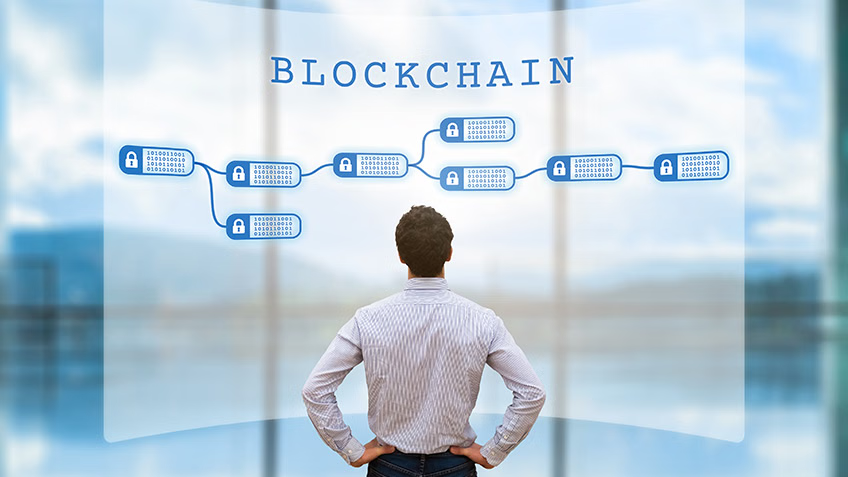

Trust has always been the foundation of human societies. Governments, financial institutions, and corporations have long acted as intermediaries, ensuring that promises are honored and agreements upheld. Yet, in today’s digital age, traditional trust structures are increasingly challenged by rising cybercrime, institutional failures, disinformation, and growing public skepticism.

In this context, blockchain technology offers a radically new way of building trust—not by relying on central authorities, but by embedding trust into code, cryptography, and decentralized networks. This article examines how blockchain reshapes governance, security, and transparency, while also addressing its limitations and future implications.

Part I: The Crisis of Trust in the Digital Era

1.1 Erosion of Institutional Trust

Surveys worldwide indicate declining confidence in governments, banks, and even news organizations. Scandals, corruption, and inefficiency have widened the gap between institutions and the public.

1.2 Vulnerabilities of Centralized Systems

Centralized databases and governance models are prone to single points of failure—whether through hacking, fraud, or abuse of power. Data breaches exposing millions of users have become a regular occurrence, demonstrating the fragility of traditional systems.

1.3 The Search for Alternatives

As society becomes more digitized, there is a growing need for systems that guarantee fairness, accountability, and security—without requiring blind trust in human intermediaries.

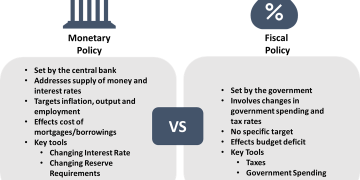

Part II: Blockchain as a Trust Machine

2.1 Transparency Through Immutable Records

At its core, blockchain is a distributed ledger where transactions are recorded immutably and publicly. This transparency ensures accountability, reducing the possibility of tampering or corruption.

2.2 Decentralization as a Safeguard

Unlike centralized institutions, blockchain spreads authority across networks of participants. This decentralization makes systems more resilient, less susceptible to manipulation, and more inclusive.

2.3 Programmable Trust with Smart Contracts

Smart contracts—self-executing agreements coded into blockchain—eliminate the need for intermediaries in enforcing rules. Whether in finance, supply chains, or legal agreements, parties can trust code rather than institutions.

Part III: Governance in the Age of Blockchain

3.1 E-Governance and Public Services

Governments worldwide are experimenting with blockchain-based systems for digital identity, land registries, and welfare distribution. For instance, Estonia has pioneered blockchain-backed e-governance platforms, enhancing both efficiency and trust.

3.2 Fighting Corruption

Blockchain’s immutability reduces opportunities for corrupt practices, especially in procurement, licensing, and record-keeping. By making processes verifiable and auditable, it empowers citizens and watchdogs to hold officials accountable.

3.3 Digital Democracy

Blockchain-enabled voting systems could increase voter participation and confidence by ensuring secure, tamper-proof elections. While still in experimental stages, such systems hold promise for revitalizing democratic governance.

Part IV: Security and Privacy

4.1 Strengthening Data Protection

Blockchain protects against unauthorized alterations, making it ideal for sensitive data such as health records or intellectual property. Unlike traditional databases, it provides cryptographic assurance of integrity.

4.2 Balancing Transparency and Privacy

One of blockchain’s paradoxes is reconciling transparency with personal privacy. Innovations like zero-knowledge proofs and permissioned blockchains aim to strike a balance, allowing verification without overexposure of personal data.

4.3 Cybersecurity Applications

By decentralizing control, blockchain reduces vulnerability to cyberattacks that typically exploit central servers. It also enables more secure digital identities and authentication systems.

Part V: Transparency in the Economy and Beyond

5.1 Ethical Supply Chains

From food safety to conflict-free minerals, blockchain ensures transparency in sourcing and production. Consumers can trace products’ origins, fostering ethical consumption and corporate responsibility.

5.2 Media and Information Integrity

Blockchain can help combat fake news by providing verifiable timestamps and sources for digital content. This could enhance trust in journalism and intellectual property rights.

5.3 Corporate Governance

Shareholder voting, auditing, and disclosure processes can be enhanced through blockchain, reducing fraud and increasing accountability within corporations.

Part VI: Challenges and Criticisms

6.1 Over-Reliance on Technology

Blockchain reduces dependence on human trust but introduces new dependencies—on algorithms, code, and infrastructure. Bugs or poorly designed protocols can undermine the very trust blockchain seeks to establish.

6.2 Energy and Sustainability Concerns

Proof-of-work blockchains consume significant energy, raising environmental concerns. More sustainable alternatives, such as proof-of-stake, are being adopted but remain under scrutiny.

6.3 Unequal Access and Digital Divide

For blockchain to deliver inclusive trust, global access to digital infrastructure is essential. Otherwise, the technology risks reinforcing inequalities rather than overcoming them.

6.4 Legal and Regulatory Complexities

Blockchain’s borderless nature clashes with jurisdiction-specific laws, raising questions about accountability, enforcement, and privacy rights.

Part VII: Looking Ahead — The Future of Trust

Blockchain is unlikely to replace traditional institutions altogether. Instead, it will coexist with them, providing a “trust layer” for the digital world. The future may see:

- Hybrid Governance Models: States and corporations integrating blockchain into existing structures for transparency and accountability.

- Trust-as-a-Service Platforms: Blockchain-powered systems offering secure verification for identities, credentials, and contracts.

- Integration with Emerging Technologies: Synergies with AI and IoT will enable autonomous systems that self-regulate and self-audit.

- Redefinition of Citizenship and Participation: Decentralized identity and voting systems may transform what it means to belong to a community or nation in the digital era.

Conclusion

Trust in the digital age cannot rely solely on institutions that are vulnerable to corruption, inefficiency, or cyber threats. Blockchain offers an alternative model, embedding trust into decentralized networks and cryptographic systems. By reshaping governance, enhancing security, and promoting transparency, blockchain has the potential to restore public confidence in systems that underpin our societies.

Yet, blockchain is not a panacea. Its success will depend on responsible design, sustainable practices, equitable access, and supportive regulation. Ultimately, blockchain’s greatest promise lies not in replacing trust but in reimagining it—building systems where transparency and accountability are embedded by design.