Introduction: Understanding the Evolution of Global Monetary Policy

Monetary policy is an essential pillar of economic governance, playing a central role in managing the supply of money, credit, and interest rates within an economy. At a global level, the evolution of monetary policy reflects a series of complex historical, political, and economic shifts. From the Gold Standard to today’s fiat currency regimes, the global monetary system has transformed significantly, and its impact is still felt today.

In this section, we will take a deep dive into the history of global monetary policy. We will analyze key historical milestones, including the emergence and eventual collapse of the Gold Standard, the post-World War II Bretton Woods system, and the transition to fiat currencies. Understanding this evolution is crucial for assessing the effectiveness and challenges of modern monetary policies across countries.

Section 1: The Gold Standard Era (Pre-World War I)

The Gold Standard was the cornerstone of global monetary systems for much of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Under the Gold Standard, the value of currency was directly tied to a specific amount of gold. This provided a stabilizing mechanism for currencies, as countries were limited in how much they could expand the money supply. The system ensured relatively stable exchange rates and allowed for the growth of global trade during the Industrial Revolution.

The Mechanics of the Gold Standard

Under the Gold Standard, nations were required to exchange their currency for a fixed amount of gold, providing a basis for international trade and capital flows. Central banks held gold reserves that acted as backing for the value of the currency. For example, if a country’s central bank held 10,000 kilograms of gold, it could issue currency worth the equivalent in value.

This system had many advantages. One of the most notable was its ability to restrict excessive money creation by governments. Since currency issuance was tied to gold reserves, it limited inflationary pressures and prevented governments from printing excessive amounts of money. It also contributed to international economic stability, as countries were forced to maintain balance of payments equilibrium to avoid depleting their gold reserves.

Limitations of the Gold Standard

Despite its benefits, the Gold Standard was not without its problems. The most significant limitation was its inability to provide flexibility in responding to economic crises. During periods of war or economic downturn, countries often needed to increase their money supply to finance military expenditures or stimulate domestic demand. However, under the Gold Standard, countries were limited in their ability to do so. If a nation ran a deficit, it would need to pay for it by drawing down its gold reserves, which could lead to economic contraction.

The inability of the Gold Standard to respond flexibly to economic crises was painfully evident during the Great Depression of the 1930s. As the world struggled to recover, many countries found that they could not stimulate their economies through monetary expansion due to the constraints imposed by the Gold Standard. This inability to act decisively led to the eventual abandonment of the system in favor of more flexible monetary frameworks.

Section 2: The Bretton Woods System and Post-War Monetary Policy

The end of the Gold Standard gave way to the Bretton Woods system, established in 1944 after the Second World War. This new system sought to provide stability to the international financial system while avoiding the rigid constraints of the Gold Standard. At the heart of the Bretton Woods system was the idea of a fixed exchange rate regime, but with an important distinction: the US dollar was pegged to gold, while other currencies were pegged to the dollar.

The Bretton Woods Framework

The Bretton Woods system created a framework where the US dollar became the primary global reserve currency, and other nations’ currencies were pegged to the dollar at fixed rates. The dollar’s convertibility into gold at a fixed price of $35 per ounce provided a stabilizing anchor for the system.

Two key institutions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, were created under the Bretton Woods Agreement to ensure financial stability and promote reconstruction in war-torn Europe and Asia. The IMF provided short-term financial assistance to countries facing balance-of-payments problems, while the World Bank funded long-term development projects.

While the Bretton Woods system brought a degree of stability to the world economy in the post-war period, it was also subject to inherent tensions. The US, as the issuer of the global reserve currency, ran persistent trade deficits that put pressure on its gold reserves. By the 1960s, the US could no longer maintain the convertibility of the dollar into gold, leading to a crisis of confidence in the Bretton Woods system.

The End of Bretton Woods and the Transition to Floating Exchange Rates

In 1971, President Richard Nixon suspended the dollar’s convertibility into gold, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system. This event, known as the “Nixon Shock,” marked the beginning of a shift towards a system of floating exchange rates. This system, which is still in place today, allows currencies to fluctuate in value based on market forces rather than being pegged to a specific asset like gold or the US dollar.

The move to floating exchange rates had profound implications for global monetary policy. It allowed central banks greater flexibility in managing their economies but also led to increased volatility in currency markets. As currencies no longer had a fixed value, fluctuations in exchange rates became a regular part of the global economy.

Section 3: The Rise of Fiat Currencies and Central Bank Independence

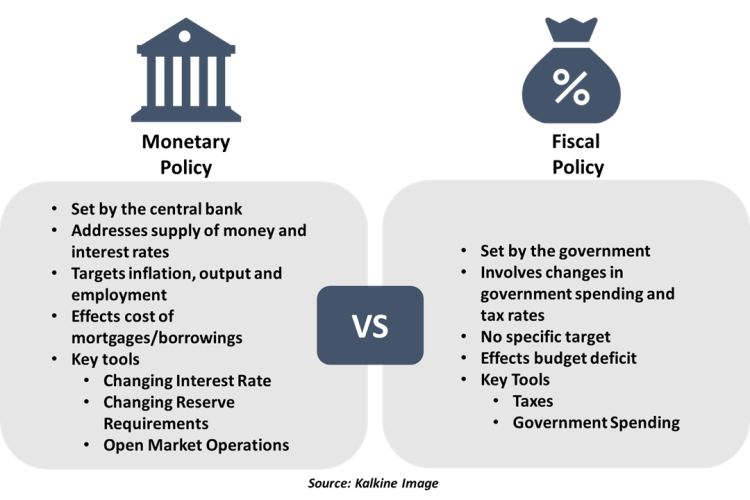

With the collapse of the Bretton Woods system and the adoption of floating exchange rates, the global economy entered a new era of monetary policy, one that relied entirely on fiat currencies. Fiat money has no intrinsic value; rather, its value is derived from the trust that people and governments place in it. Central banks gained greater control over their monetary systems, using a variety of tools such as interest rates, reserve requirements, and open market operations to manage inflation and stabilize their economies.

The Role of Central Banks

One of the most significant developments in modern monetary policy has been the growing independence of central banks. Throughout much of the 20th century, central banks operated under the direction of government authorities. However, the growing recognition of the importance of independent monetary policy led many countries to grant their central banks greater autonomy.

The independence of central banks, especially in countries like the United States (Federal Reserve) and the European Union (European Central Bank), has played a crucial role in maintaining low inflation and long-term economic stability. Central banks are now able to focus on managing inflation and stabilizing prices without being subject to short-term political pressures.

Monetarism and the Fight Against Inflation

The 1970s saw a shift in monetary policy with the rise of monetarism, championed by economists such as Milton Friedman. Monetarists argued that inflation was primarily the result of excessive growth in the money supply. In response, central banks, particularly in the United States, adopted policies aimed at controlling money supply growth to reduce inflation. This approach, known as the “monetary targeting” strategy, was used effectively in the early 1980s by then-Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker to combat the high inflation of the 1970s.

The success of these policies in bringing inflation under control solidified the role of central banks as independent institutions committed to price stability.

Section 4: The Globalization of Monetary Policy

As the world economy became more integrated in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, monetary policy became increasingly influenced by global economic conditions. The rise of international trade, capital flows, and financial markets meant that decisions made by central banks in one country could have far-reaching effects on other economies.

The Impact of Globalization on Monetary Policy

Globalization has created both challenges and opportunities for central banks. On one hand, central banks in advanced economies, such as the US and the European Union, face the challenge of managing monetary policy in a world of increasingly mobile capital. Interest rate decisions in one country can quickly affect exchange rates, investment flows, and inflation expectations around the world.

On the other hand, globalization has also led to greater cooperation among central banks. Institutions like the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) facilitate dialogue and coordination among central banks, especially during times of global financial crises.

The 2008 Financial Crisis and the Role of Central Banks

The global financial crisis of 2008 was a defining moment for central banks worldwide. In response to the crisis, central banks adopted unprecedented measures, such as zero interest rates, quantitative easing, and large-scale government bailouts of financial institutions. These measures were necessary to prevent a global depression but also highlighted the growing influence of central banks in managing global economic stability.

Central banks also learned important lessons from the 2008 crisis, including the need for greater coordination and regulation of global financial markets. Today, central banks are actively working to strengthen financial stability frameworks and prepare for potential future crises.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Evolution of Global Monetary Policy

The history of global monetary policy is a story of adaptation to economic, political, and technological changes. From the rigidity of the Gold Standard to the flexibility of modern fiat currency systems, the evolution of global monetary policy reflects the changing needs of economies and the challenges of an increasingly interconnected world.

As we move forward, the role of central banks will continue to evolve. While they must maintain their traditional goals of price stability and economic growth, they must also address new challenges, including financial market volatility, income inequality, and climate change. The future of global monetary policy will require central banks to balance flexibility with stability, ensuring that their actions contribute to long-term economic well-being.