Introduction: Understanding Modern Monetary Policy

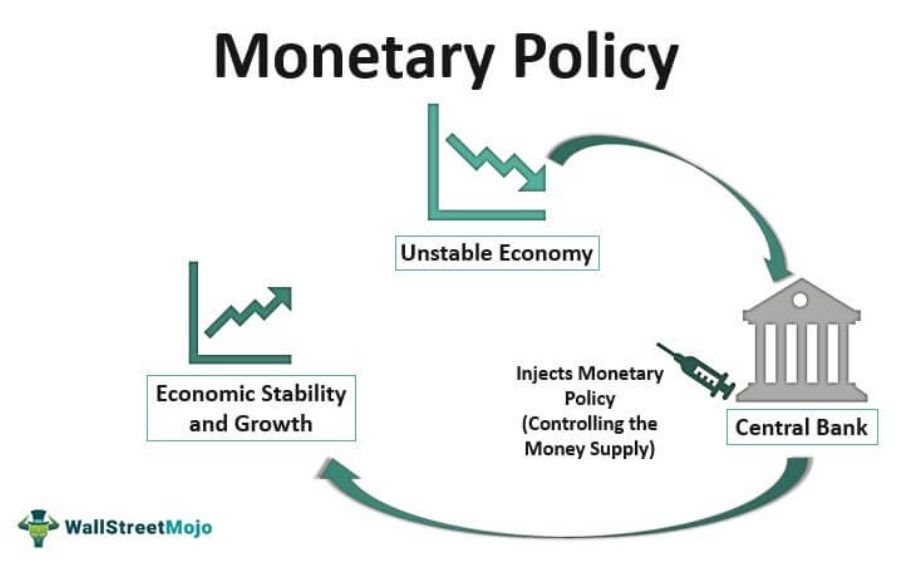

Monetary policy is one of the most critical tools in the economic toolkit of central banks, allowing them to influence the broader economy. Over the years, the methods and objectives of monetary policy have evolved, especially with the advent of new economic theories and practices. Today, central banks use an array of tools to achieve their primary targets of price stability, full employment, and economic growth.

The complexity of modern economies requires central banks to constantly adapt their policies in response to both global and domestic changes. This article will explore the tools that central banks use in contemporary monetary policy, the targets they strive to meet, and the various challenges they face in achieving their objectives.

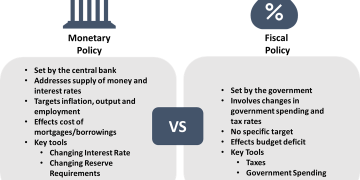

Section 1: The Tools of Modern Monetary Policy

Central banks have a variety of tools at their disposal to influence the economy. These tools can be broadly categorized into traditional and non-traditional methods. Below, we will delve into each tool in greater detail.

Interest Rates: The Primary Tool

Historically, adjusting interest rates has been the central tool for managing the economy. Central banks influence short-term interest rates, typically through a benchmark rate, such as the Federal Funds Rate in the United States. Changes in interest rates have direct implications for borrowing costs for businesses and consumers, which in turn affects aggregate demand.

When central banks lower interest rates, borrowing becomes cheaper, leading to increased investment and consumer spending. Conversely, when interest rates are raised, borrowing becomes more expensive, which slows down inflationary pressures and curtails economic overheating.

The effectiveness of interest rates depends on the state of the economy. For example, in a low-interest-rate environment, further cuts may have limited effects if businesses and consumers are unwilling to borrow. This issue has become increasingly relevant in recent years, especially in advanced economies where interest rates have remained near zero or even negative for prolonged periods.

Open Market Operations (OMO)

Open market operations are another critical tool central banks use to regulate the money supply and control short-term interest rates. In OMO, central banks buy or sell government securities in the open market. By purchasing securities, central banks inject money into the economy, which stimulates economic activity. Conversely, selling securities reduces the money supply and can help cool down an overheating economy.

OMO is used to manage liquidity in the financial system, which is essential for ensuring that short-term interest rates remain within the target range set by the central bank. During times of financial crisis or instability, central banks may increase the scale of their OMO operations to ensure that financial markets remain liquid and that borrowing costs do not rise excessively.

Quantitative Easing (QE)

Quantitative easing became a prominent tool after the global financial crisis of 2008, when traditional interest rate policy reached its limits. When central banks face the zero-lower-bound (ZLB), where interest rates are near zero, they may turn to QE, which involves large-scale purchases of financial assets such as government bonds and mortgage-backed securities.

The goal of QE is to lower long-term interest rates, increase the money supply, and encourage lending and investment. While QE can be effective in stimulating demand in the short term, it also raises concerns about asset bubbles, income inequality, and potential long-term inflationary pressures. The scale and duration of QE programs have also sparked debates about whether they distort markets and create excessive risks for the financial system.

Forward Guidance

Forward guidance is a more recent tool that central banks use to shape expectations about future monetary policy. By providing clear signals about the direction of interest rates or the likely duration of accommodative policies, central banks can influence investor, business, and consumer behavior in the present.

Forward guidance is especially effective when interest rates are at or near zero, as it can provide additional clarity and reduce uncertainty. However, the effectiveness of forward guidance relies on the central bank’s credibility and the accuracy of its economic forecasts. If expectations about future policy diverge from actual outcomes, it can lead to volatility in financial markets.

Reserve Requirements

Reserve requirements refer to the percentage of deposits that commercial banks are required to hold in reserve, either as cash or deposits at the central bank. Lowering reserve requirements increases the money supply by allowing banks to lend more, whereas raising reserve requirements reduces the money supply by forcing banks to hold more capital.

While this tool is not frequently used in modern monetary policy, central banks may adjust reserve requirements during periods of extreme economic stress. In the past, reserve requirements were a critical tool for managing banking sector liquidity and controlling inflation, but the increasing complexity of global finance has made it less relevant in contemporary monetary practice.

Section 2: Targets of Modern Monetary Policy

The central objectives of modern monetary policy are generally aligned with promoting economic stability and growth. However, these targets have evolved over time, and central banks are now expected to manage several goals simultaneously.

Price Stability

One of the most important objectives of modern monetary policy is to maintain low and stable inflation. Price stability ensures that the purchasing power of a country’s currency remains relatively constant, which is essential for economic planning and long-term investment.

Most central banks target a specific inflation rate, often around 2%. The rationale behind this target is to avoid both runaway inflation, which erodes purchasing power and creates economic uncertainty, and deflation, which can lead to stagnation and lower economic activity.

Full Employment

Full employment is another key objective of central banks. While central banks cannot directly control employment levels, they can influence economic conditions that foster job creation. By lowering interest rates and increasing the money supply, central banks can encourage businesses to invest, which can lead to more jobs in the economy.

However, achieving full employment without triggering inflation remains a delicate balance. If the economy operates at full capacity for too long, it may lead to wage inflation and higher consumer prices. Central banks must monitor the labor market closely and adjust policy accordingly to ensure that employment levels remain sustainable.

Economic Growth

Promoting sustainable economic growth is a crucial goal of monetary policy. Central banks strive to foster an environment that encourages investment, innovation, and entrepreneurship. By providing stable financial conditions and managing inflation, central banks aim to create an economic climate conducive to long-term growth.

While monetary policy alone cannot drive economic growth, it plays a supportive role by ensuring low and predictable inflation and by preventing excessive volatility in financial markets. Central banks also adjust their policies to respond to external shocks, such as recessions or financial crises, to minimize the negative impact on growth.

Financial Stability

Financial stability has become an increasingly important target for central banks in the wake of the global financial crisis. Ensuring that financial markets operate smoothly and that banks remain solvent is essential for the health of the economy. Central banks play a key role in regulating financial institutions, managing systemic risk, and preventing financial panics.

In recent years, central banks have also focused on macroprudential policies, which are designed to address risks that may threaten the stability of the financial system as a whole. This includes monitoring systemic risks, managing credit bubbles, and ensuring that financial institutions hold adequate capital buffers.

Section 3: The Challenges Facing Modern Monetary Policy

Despite the sophisticated tools available to central banks, there are several significant challenges to effective monetary policy.

Globalization and Interconnectedness

In today’s globalized economy, central banks must consider not only domestic conditions but also international trends. The interconnectedness of global financial markets means that decisions made by central banks in one country can have ripple effects across the globe. For example, changes in US interest rates can influence capital flows and currency valuations in emerging markets.

Moreover, central banks must contend with the impact of trade policies, geopolitical risks, and global supply chains. These factors often complicate their efforts to achieve domestic policy goals, as external shocks can undermine domestic stability.

The Zero Lower Bound (ZLB)

The zero-lower-bound problem arises when interest rates are close to zero, limiting the ability of central banks to stimulate the economy through traditional interest rate cuts. This was particularly evident during the global financial crisis of 2008, when many central banks had already reduced interest rates to historically low levels.

To address this issue, central banks have turned to unconventional tools such as QE and forward guidance. However, the effectiveness of these tools remains uncertain, and their long-term consequences are still being debated.

Asset Bubbles and Financial Instability

Low interest rates and abundant liquidity can lead to the formation of asset bubbles in real estate, stocks, or other markets. While central banks aim to prevent bubbles from forming, they face challenges in detecting and deflating them before they burst.

The global financial crisis of 2008 was a stark reminder of the dangers posed by unchecked financial excesses. Central banks must balance the need to stimulate economic activity with the risk of creating financial instability.

Income Inequality

Critics of modern monetary policy argue that policies like QE and low interest rates disproportionately benefit the wealthy, exacerbating income inequality. By inflating asset prices, these policies have contributed to rising wealth disparities, as those with assets benefit from increased valuations, while those without assets see limited gains.

Central banks are increasingly aware of these concerns and are exploring ways to address the distributional effects of monetary policy. However, finding a solution that maintains economic stability while reducing inequality is a complex and ongoing challenge.

Conclusion: The Future of Modern Monetary Policy

Modern monetary policy has come a long way from the simple tools of the past. Today, central banks use an array of sophisticated methods to manage inflation, promote economic growth, and maintain financial stability. However, as the global economy becomes more complex and interconnected, central banks face new challenges that require innovative solutions.

Moving forward, central banks will need to remain agile in response to changing economic conditions, technological advancements, and global challenges. The future of monetary policy will depend on a careful balance between promoting growth and maintaining stability, while addressing the broader social and economic implications of their actions.