Introduction: The Political Economy of a Digital World

The Metaverse is often imagined as a playground of immersive entertainment and social connection. Yet, beneath the surface lies a deeper transformation: the emergence of virtual economies and the reconfiguration of digital sovereignty.

As nations, corporations, and communities stake claims in these expanding digital territories, questions arise: Who owns the data? Who governs virtual interactions? And how will the distribution of wealth and power shift in the Metaverse era?

This essay examines the geopolitics of the Metaverse, focusing on economic systems, digital sovereignty, and the balance of global power.

1. The Rise of Virtual Economies

1.1 Economic Foundations of the Metaverse

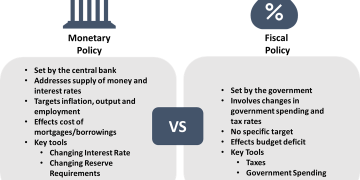

- Virtual economies mimic physical ones: production, trade, consumption, and ownership.

- Digital assets (NFTs, cryptocurrencies) provide value systems and markets.

1.2 Virtual Labor and Digital Commodities

- Millions already earn income through virtual platforms (streaming, digital design, in-game trade).

- Metaverse-native labor markets: virtual architects, event organizers, avatar stylists.

1.3 The Scale of Value Creation

- Analysts predict the Metaverse economy could reach trillions of dollars by 2030.

- Virtual real estate sales (Decentraland, Sandbox) illustrate speculative dynamics.

2. Digital Sovereignty in Virtual Spaces

2.1 Defining Digital Sovereignty

- Control over data, infrastructure, and digital citizens.

- Extends traditional sovereignty into the virtual domain.

2.2 Corporate vs. State Authority

- Big Tech companies (Meta, Microsoft, Tencent) dominate platforms, raising governance concerns.

- Governments attempt to regulate virtual assets, taxation, and online rights.

2.3 Data as a Geopolitical Asset

- In immersive environments, user data includes biometric, behavioral, and cognitive patterns.

- Control over this data becomes a strategic resource comparable to oil in the 20th century.

3. Geopolitical Dynamics of the Metaverse

3.1 U.S.–China Competition

- U.S. leads in platform development; China emphasizes digital sovereignty and regulatory frameworks.

- Competing models: open innovation vs. state-controlled digital ecosystems.

3.2 The European Union’s Regulatory Push

- EU champions digital rights and privacy (GDPR as precedent).

- Promotes a vision of a “human-centered” Metaverse with ethical safeguards.

3.3 Global South and Digital Inclusion

- Developing nations face infrastructure gaps but seek opportunities in virtual economies.

- Risk of digital colonialism if access and governance remain dominated by wealthy nations.

4. Case Studies in Virtual Geopolitics

Case 1: Cryptocurrency and Metaverse Trade

- Crypto enables borderless transactions but challenges monetary sovereignty.

- El Salvador’s Bitcoin adoption illustrates risks and possibilities.

Case 2: Digital Borders and National Regulation

- China’s “Great Firewall” approach extends to virtual platforms, shaping localized Metaverses.

- Raises questions about the fragmentation of the global digital commons.

Case 3: Corporate Governance of Virtual Worlds

- Decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) experiment with self-governance.

- Contrast with centralized platforms that control rules and monetization.

5. Risks and Challenges

- Economic Inequality: Concentration of wealth in digital elites and corporations.

- Cybersecurity: Virtual economies vulnerable to hacks, fraud, and systemic risks.

- Legal Ambiguity: Ownership disputes, intellectual property conflicts, taxation challenges.

- Cultural Sovereignty: Dominant cultural models embedded in virtual worlds may marginalize local traditions.

6. Future Scenarios: Geopolitics in the Metaverse Era

6.1 Scenario A: Corporate Dominance

- Tech giants control virtual economies, shaping governance and culture.

- Governments remain reactive regulators.

6.2 Scenario B: State-Controlled Metaverses

- Nations build walled digital gardens reflecting political models.

- Fragmentation of the global Metaverse into competing blocs.

6.3 Scenario C: Decentralized Digital Commons

- Open-source, community-led Metaverses ensure inclusivity and democratic governance.

- Requires global collaboration to succeed.

Conclusion: Power, Identity, and the New Digital Frontier

The Metaverse is not just a technological evolution; it is a new arena of geopolitical competition. Virtual economies generate immense value, while digital sovereignty redefines the authority of states and corporations.

The trajectory of the Metaverse era will depend on whether humanity embraces a cooperative, inclusive vision or succumbs to fragmented, monopolistic control.

Just as industrial revolutions reshaped global power in the past, the rise of the Metaverse will determine the winners and losers of the digital future. Managing this transition wisely requires foresight, ethical governance, and a commitment to protecting both economic equity and cultural diversity.