Opening Perspective

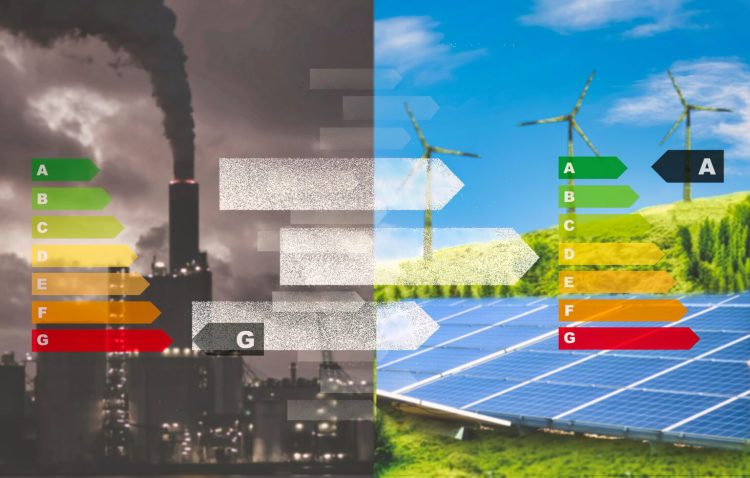

Energy defines civilizations. Coal fired the steam engines of the Industrial Revolution, oil fueled the twentieth century’s cars and airplanes, and natural gas powered homes and industries. These resources shaped economies, politics, and wars. Yet today, fossil fuels stand accused: of polluting the air, destabilizing the climate, and threatening the very ecosystems that sustain humanity.

At the same time, renewables—solar panels glittering on rooftops, turbines rising on windy coasts, and hydro dams capturing river flows—have emerged as the new promise. They represent not only cleaner power but also new economic models, distributed energy systems, and opportunities for justice.

The transition from fossil fuels to renewables is therefore more than a technological shift; it is a societal transformation. But it is not straightforward. It is shaped by obstacles—political, economic, technological, and cultural—and by enormous opportunities that can redefine the future of humanity.

The Fossil Fuel Legacy

Benefits Brought by Fossil Fuels

- Energy abundance: Coal, oil, and gas created the industrial economy.

- Scalability: Fossil fuels supported large cities and global supply chains.

- Economic growth: Fossil industries provided millions of jobs.

- Global trade: Oil, in particular, shaped world markets and alliances.

The Costs We Now See

- Climate change: Fossil fuels account for nearly 75% of greenhouse gas emissions.

- Health crises: Air pollution kills millions annually.

- Geopolitical risks: Dependence on oil and gas imports fuels global conflicts.

- Resource depletion: Extractive industries often leave behind ecological scars.

Thus, the same fuels that powered human progress also created a planetary crisis.

Renewables: The Rising Force

Unlike fossil fuels, renewables are:

- Clean: No direct emissions from wind, solar, or hydro.

- Infinite: Sunlight, wind, and water are naturally replenished.

- Decentralized: Can empower communities, not just corporations.

- Flexible: Integrated with digital technologies for smart grids.

But they are also:

- Intermittent: Dependent on weather and seasons.

- Resource-intensive: Require critical minerals like lithium and cobalt.

- Unevenly distributed: Sun-rich deserts differ from cloudy northern regions.

Renewables are not a perfect substitute—they require systemic changes to how we design, govern, and consume energy.

The Key Challenges

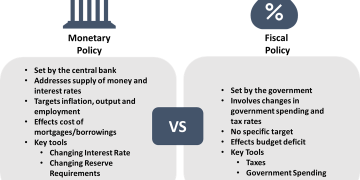

- Technological Barriers

- Energy storage remains costly.

- Grid infrastructure lags behind renewable adoption.

- Hydrogen and carbon capture are promising but not yet mature.

- Economic and Financial Issues

- Transition requires trillions in investment.

- Fossil subsidies still outweigh renewable subsidies in many countries.

- Developing nations face difficulties accessing green finance.

- Social and Political Resistance

- Workers in fossil industries fear job losses.

- Oil-rich states resist policies that undermine their economies.

- Local communities often oppose large-scale wind or hydro projects.

- Geopolitical Uncertainty

- Fossil fuel exporters risk instability if revenues collapse.

- Critical minerals could create new geopolitical rivalries.

- Global governance on climate remains fragmented.

The Emerging Opportunities

Despite challenges, the opportunities are transformative:

- Economic Renewal

- Renewable industries are labor-intensive, creating jobs in construction, maintenance, and innovation.

- Green sectors attract massive private investment and venture capital.

- Energy Security

- Renewables reduce dependence on imported fuels.

- Countries can generate power domestically, boosting resilience.

- Technological Leadership

- States leading in battery storage, hydrogen, or smart grids will dominate future markets.

- The clean tech race could be as defining as the space race.

- Social Justice

- Off-grid solar brings electricity to rural villages.

- Community-owned projects empower marginalized groups.

- Just transition policies can protect vulnerable workers.

Comparative Cases

Germany: Ambitious but Uneven

Germany’s Energiewende policy became a global model. It massively scaled solar and wind but struggled with high energy prices and reliance on coal during transition gaps.

China: Scale at Speed

China produces most of the world’s solar panels and dominates EV manufacturing. Yet it still burns half the world’s coal, highlighting the contradictions of rapid growth.

United States: Innovation-Driven

With the Inflation Reduction Act, the U.S. pumped billions into clean energy. Innovation in AI-managed grids and storage keeps it competitive, but political divisions remain.

Africa: Potential Untapped

Africa has 60% of the world’s solar potential yet less than 1% of installed solar capacity. Financing and infrastructure gaps remain the key barriers.

Human Dimension: Winners and Losers

- Winners: Renewable industries, technology innovators, forward-looking investors, and rural communities gaining energy access.

- Losers: Coal miners, oil-export-dependent economies, and traditional utilities resisting change.

The energy transition is not just an engineering challenge; it is a moral and political negotiation about fairness, inclusion, and responsibility.

The Future Landscape: Possible Pathways

- Rapid Transition (Optimistic)

- Renewables dominate by 2040.

- Net-zero achieved mid-century.

- Global cooperation drives innovation and equity.

- Uneven Transition (Moderate)

- Developed countries decarbonize faster.

- Developing nations struggle with financing.

- Fossil fuels remain significant in Asia and Africa.

- Stalled Transition (Pessimistic)

- Fossil fuels dominate through 2050.

- Climate disasters worsen inequality.

- Green technology becomes a tool of great-power rivalry.

Opportunities to Seize Now

- Reform subsidies: Redirect from fossil to renewable support.

- Invest in grids: Build digital, smart, and flexible networks.

- Expand global cooperation: Share green technology across borders.

- Promote circular economy: Recycle batteries and critical minerals.

- Ensure justice: Support workers and communities in fossil regions.

Concluding Reflections

The shift from fossil fuels to renewables is the defining journey of our century. It is not a straight road but a contested, uneven, and deeply political process. Yet it is also humanity’s greatest chance: to align energy with sustainability, to pair growth with responsibility, and to redefine prosperity beyond carbon.

If the world seizes this opportunity, future generations may look back and see the early twenty-first century as the moment when humanity finally learned to power civilization without destroying its home.